Togo’s tale: Former Bridge City, Port Neches-Groves coach Railey shares place in NCAA history

Published 9:46 pm Saturday, April 2, 2016

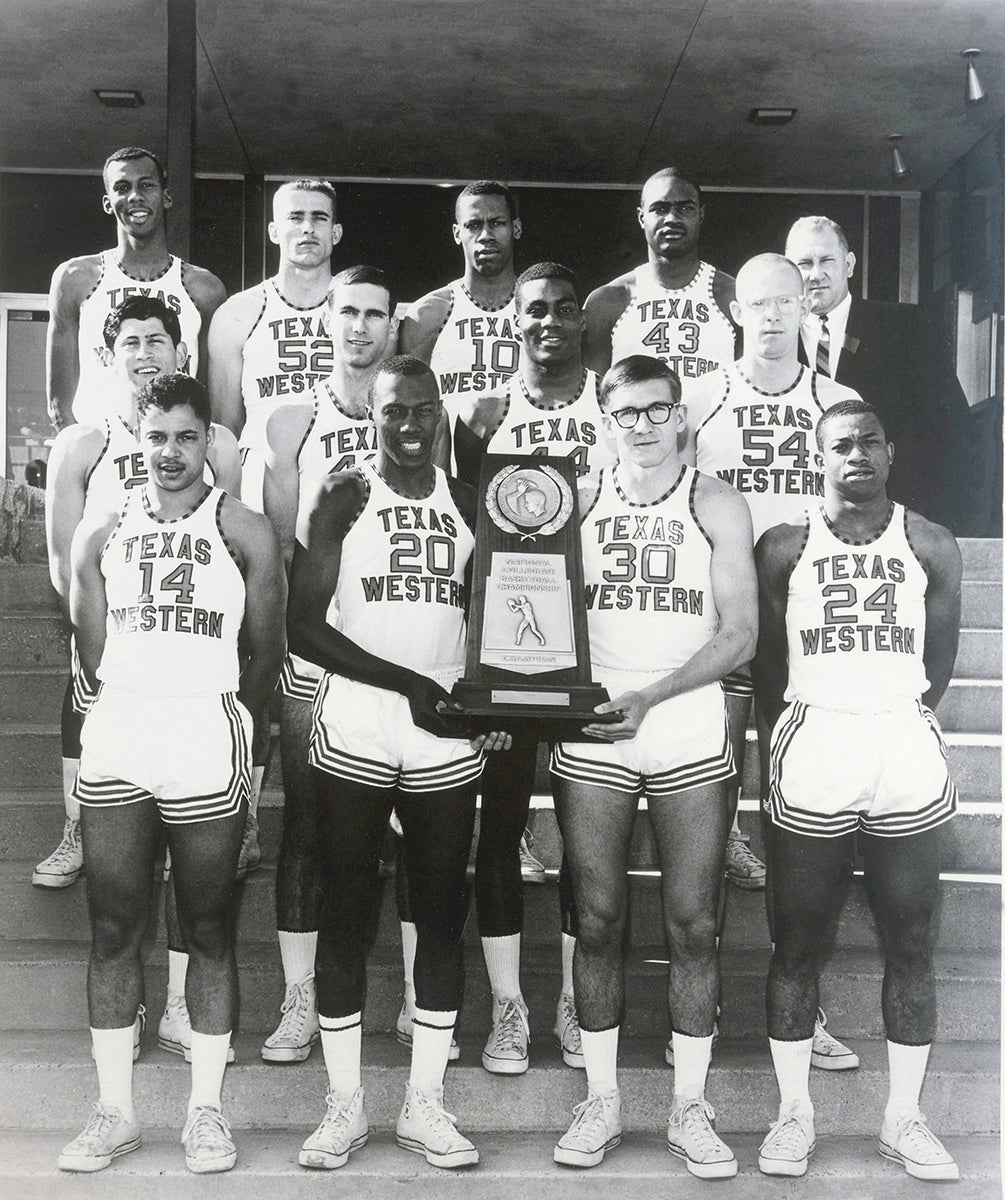

- Togo Railey (30) poses in the 1966 Texas Western team photo after the Miners won a historic NCAA championship final over Kentucky. (UTEP sports information)

If there’s one person Togo Railey tried to emulate in his coaching career, it was Don Haskins.

“The first year as a coach, you couldn’t have told me a thing,” the former Texas Western basketball player said. “I knew everything from college. I was brutal because Haskins was brutal. …

“Until I learned to coach my personality and use the fundamentals I had, … I couldn’t be a Haskins. As soon as I learned to relax and be with the players you have, it was so much enjoyable.”

Railey did find success coaching at Bridge City and Port Neches-Groves schools from 1973-86, but not many immediately knew that he was a part of a historic national championship team under Haskins a few years earlier. The Texas Western College (now University of Texas at El Paso) Miners became the first team to win the NCAA men’s basketball championship with an all-black starting lineup.

Railey, who played high school ball in El Paso, was one of five white players on that ballclub and saw limited action in three varsity seasons.

“I did not know him until he came to the area,” said former PN-G High School coach Phil Vergara, who worked with Railey through the early 2000s.

“He’s not a bragger, real down to earth,” Vergara said. “Real slow paced. If you eat, you better be ready to eat for 2 or 2½ hours because he’ll take his time and chew and eat.”

•

Togo Railey was born Albert Tolton Railey and grew up in Columbia, Missouri, where he learned the fundamentals of basketball from an elementary coach named Norm Stewart in the 1950s. Stewart is best remembered for a storied 32-year career coaching the Missouri Tigers, where he won 634 games and coached in 16 NCAA Tournaments.

During his school days, Railey was introduced before a game when the public address announcer mispronounced Tolton, which he was called as a youngster, as “Togo.” The name stuck.

The Raileys moved to El Paso, where Togo finished high school in 1962. He passed up a partial scholarship to Texas Tech and a full ride to smaller Trinity University to walk on to the basketball program at Texas Western as a freshman. (Freshmen had their own team at the time as the NCAA did not allow such players to compete on the varsity level.)

Railey’s goal at the time was to become a mining engineer, and the school has its origins in mining and metallurgy education.

“I walked on as a freshman, was lucky enough to get a scholarship as a sophomore, then took off a year as a mining engineer student in New Mexico,” Railey said. “I changed my major two or three times and finally decided to get into physical education. Got a BS in physical education then got an MS in PE and mid-management certificate at Lamar University.”

Railey returned to Texas Western from New Mexico in 1965 and resumed his basketball scholarship with two years of eligibility remaining.

Haskins had established a consistent winner in El Paso by this time, having gone 78-25 with two appearances in the NCAA Tournament and another in the National Invitation Tournament in four seasons. The next season, their last under the Texas Western name, the Miners would change the landscape of college basketball forever.

•

As the first basketball program in Texas to racially integrate, according to Railey, the Miners tackled racism on their path to greatness, although not many outside El Paso initially took notice.

“No one really pays attention to what happens in El Paso,” Railey said. “We played Arizona and Arizona State, and they had black athletes. Where we ran into trouble was with teams from Commerce [present-day Texas A&M University-Commerce was East Texas State University at the time], Texas Tech and Arkansas. Even Dallas was pretty radical [against integration]. We were just trying to win ballgames. We played Commerce, but we didn’t play in Commerce, so we didn’t have to worry about that.”

One of Texas Western’s all-time greats, Jim Barnes, hailed from Arkansas and graduated right after Railey’s second year there. (Another Miner great, Nolan Richardson, became the first black head coach at the University of Arkansas in 1985.)

“When we recruited [Barnes], we tried to get a game close to his home in Tuckerman so his folks could see him,” Railey said. “The closest school was Arkansas State. … We flew up to Jonesboro. We got to the airport about 6:30. They wouldn’t hold the game for us. We dressed in the hangar, took the taxi and walked to the floor.

“We were in a hotel, and they wouldn’t give us any rooms. We had already had reservation, and Haskins said, ‘No, we’re staying here.’ The hotel said they were booked up. That was the first real prejudice we faced.”

The 1965-66 Miners had a 23-0 record and No. 2 national ranking going into their final regular-season game, when they lost at Seattle 74-72. The Miners still had earned a bid to the NCAA Tournament and were placed in the Midwest Regional, where they beat Abe Lemons-coached Oklahoma City (now an NAIA program) and had to survive two overtime games against Cincinnati and Kansas to reach the national semifinals at the University of Maryland.

•

Texas Western beat Utah 85-78 and No. 1-ranked Kentucky shook off Duke 83-79 on March 18 inside Cole Field House in College Park to meet the next night for the championship. At this time, the NCAAs were not yet nationally televised, all-session tickets to the game reportedly topped $50, and “Final Four” had not yet become the official name for the championships. (There was even a third-place game, which Duke won 79-77 over Utah, but the NCAA eliminated that consolation bout after 1981.)

Behind Bobby Joe Hill’s 20 points, David Lattin’s 16 and Orsten Artis’ 15, the Miners defeated all-white Kentucky 72-65 before a crowd of 14,253. Pat Riley and Louie Dampier each led the Wildcats with 19 points, while Larry Conley added 10. Lattin (nine rebounds), Dampier (nine) and Conley (eight) came close to double-doubles. The game report from the Associated Press made no mention of the historical significance of the Miners’ win.

Railey did not make the box score that night. In fact, he saw limited action during his varsity career.

“I could have probably played anywhere else and started, but not at UTEP,” he said. “We had some good kids. They were good from the get-go. I was a marginal player. I walked on, busted my ass every day. I kept my nose clean. I played every game as a freshman, as a sophomore probably played 16 games in ’64, played four games in 1966 and played eight games in 1967.”

Railey graduated from UTEP in 1968 and began his coaching career in the junior high ranks in Odessa and Midland. He was hired to take over the JV team and coach football linebackers at Bridge City High in 1973 and was elevated to head basketball coach the next year.

“There were only 11 basketball players at the whole high school when I got there,” Railey said. “I saw the kids in the band. The band kids were beautiful kids, 6-3 and 6-4. They almost fired me the first week because I was chasing down the band kids.

I begged the kids to play.”

Railey built the Cardinals into a winning team and had drawn 58 kids into his program when he became the varsity coach. They won nine games in 1974-75 and started 14-2 the next season before dropping seven of eight district games.

“We made some improvements,” he said.

Railey then moved to Port Neches Middle School while Vergara was still the high school head coach. They ended up working together at the middle school before Railey became JV coach and linebackers coach at PN-G High in 1982. He held those positions before he became assistant principal at Port Neches Middle in 1986.

Railey moved back to El Paso after his 2004 retirement from Port Neches. Kip Wells portrayed Railey in the 2006 movie “Glory Road,” which told the story of the title team.

In 2007, the entire 1965-66 Miners team was enshrined in the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame. Haskins died in 2008.

A dinner commemorating their 50th anniversary was held Friday night in Houston in conjunction with the Final Four. They were to be honored at halftime of Saturday’s semifinal between Oklahoma and Villanova in NRG Stadium and will be celebrated again at halftime of Monday’s championship, as the new Hall of Fame class is announced. Lattin’s grandson Khadeem, who is from Houston, is a sophomore forward at Oklahoma.

While not many knew of Railey’s place in history, being a part of history followed him his entire career.

“It kind of follows you whenever you apply for a job,” he said. “Of course, coach Haskins was on my resume. … Soon as you graduated, you were all-American. He took care of you.”