WWII pilot marks 72nd anniversary of being shot down

Published 11:54 am Tuesday, May 31, 2016

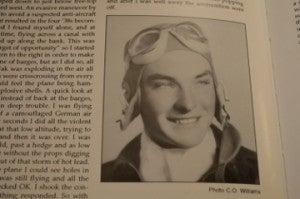

- Clifford Williams, who served in the U.S. Army Air Forces, holds a replica of the B-38 plane he flew during World War II. Mary Meaux/The News

NEDERLAND — Time and age may have stolen some of Clifford Williams’ memory and his hearing, but the story of his actions during World War II stay alive through his son and earlier published materials.

Like older veterans, Williams did not typically speak about the horrors of war, Charlie Williams, his son, said.

“When I was a little kid, he didn’t talk about that kind of stuff,” his son said. “It wasn’t until I was in elementary school that I learned he had been shot down.”

Friday, May 27, marked the 72 anniversary of that fateful day. At that time Clifford Williams was a first lieutenant in the U.S Army Air Forces. His tales include being shot down by the Germans, being saved by a group of people with the French Resistance and being forced to dig his own grave. He was later reunited with the man who saved his life.

Seated outside Williams’ Nederland home, son Charlie Williams told his father’s story.

Clifford Williams, now 94, was born in Village Mills in the Silsbee area and joined the military before the start of WWII when he realized he couldn’t find a job.

“They told the recruits they would train them for a job and dad wanted to be a mechanic, so he went to mechanic school,” Charlie Williams said.

With the urging of a fellow soldier, Williams enrolled in pilot school.

“He had tales of ship convoys going across the Atlantic, and the ship they were on had mechanical problems and was left behind. Once the ship was fixed, it caught up to the convoy,” he said. “At that time everybody had to be on deck in case of a torpedo. They were up there one day and all of a sudden one of those ships blew up about a quarter of a mile away.”

Clifford Williams flew a B-38 and was tasked with escorting bombers. Fighter planes such as his dad’s did their duty then peeled off quickly. He was in a formation of four and was supposed to head back to England, but on his 10th mission there were problems.

“He was flying low level and spotted an anti-aircraft tower. The planes were to split apart but someone made the wrong break and dad had to cut under,” he said, adding that the three other pilots reported back to England thinking Williams had crashed and died. “He was on his own and ended up flying down a German airfield. As soon as he realized this, he started seeing machine gun tracers. He banked his plane so there was an engine between them (him and machine gun fire) and his left engine was all shot to hell. There were fields all around, some with beets, and he was able to put the plane down without crashing it.”

When the elder Williams got out of his cockpit, he was met by two young French teenagers who brought him to a wooded area, switched clothes with him and gave him a bicycle to ride.

“As he headed down the road, a German patrol truck passed by headed to the wreck site. He hid in a culvert overnight.”

The teens brought the downed pilot to a brave group of underground rebels, the French Resistance. The son thought back to the enormity of the situation.

“Just moving around at night, you could get yourself shot, Charlie Williams said. “Things were hard for the underground operators. Germans killed people on a regular basis and were suspicious of the underground activities.”

The elder Williams was hidden in the home of Madame Cresson. Her son, Pierre Cresson, had been in the French Army before the defeat by the Germans and would go speak to him, but there was a language barrier. After a while Pierre Cresson became suspicious and thought Williams was a spy trying to infiltrate the resistance.

“Pierre gave my dad a shovel and indicated he wanted him to start digging, and dad realized they were going to kill him,” the son said. This went back and forth for a while and Williams gave the shovel back and told Cresson to dig the hole himself.

The American pilot and the Frenchman later began to trust each other and the Frenchman would bring Williams out to show him telephone lines the resistance was going to blow up.

Williams was moved around for some time until he was liberated when the allies pushed across France. Because of his time spent with the underground, he wasn’t allowed to fly back home in case he was shot.

In later years Williams shared with his children some of the sadness he saw during the war. The father described how each bomber plane was outfitted with a crew of 10 men, and at times there would be a 20-mile long train of bombers hitting cities for hours.

“One of the most pitiful things he saw, seeing bombers shot out of the sky, blown up, and he knew each plane was carrying 10 men.”

Williams later went on to start a career at a local refinery, marry and start a family. He became associated with the Air Forces Escape and Evasion Society, a group encouraging airmen who were aided by resistance organizations or patriotic nationals of foreign countries to continue friendships with those who helped them.

“Dad and mom would go to these AFEES reunions and all these guys were there with similar situations. Everybody there had a tale,” the son said. “It was like a league of extraordinary gentlemen. You’d be around all these guys on an even plane, but they’d still be two levels above you.”

In the mid-1980s Williams was asked to appear on a French television show that reunited people who hadn’t seen each other in a long time. Cresson had been looking for him, Charlie Williams said.

“The Frenchman who had hidden him was trying to get in touch with him. He’d been to the United States a time or two. He not only helped dad but a whole group of pilots who were downed.”

Williams appeared on the show and was reunited with Cresson and was able to revisit some of the areas he had not seen since the war.

John DeVillier of Groves worked at the same refinery as Williams, but in a different department. He wasn’t aware of the former pilot’s story until someone tipped him off. DeVillier met with Williams and told his tale of rescue and the appearance on French TV which was published in the company newsletter.

“I remember his comment,” DeVillier said. “The real heroes were the people of France who put their lives on the line to rescue Allied airmen and hide them from the Germans.”

Williams became emotional, DeVillier said, when talking about the German soldiers leaving town.

“Four months after the forced landing in northern France, I watched from a second-story window as the Germans began a full scale retreat toward the Rhine. For two days and two nights they pulled back. Then it was like a vacuum. There wasn’t a sign of life for 24 hours. Nothing stirred. Suddenly, American tanks clattered through the streets and the town became alive. There were French, American and British flags everywhere. I’ll never forget the feeling,” Clifford Williams told DeVillier.

Mary Meaux: 409-721-2429

Twitter: @MaryMeauxPANews