Judge Donald Floyd looks back on career

Published 10:27 am Monday, December 31, 2018

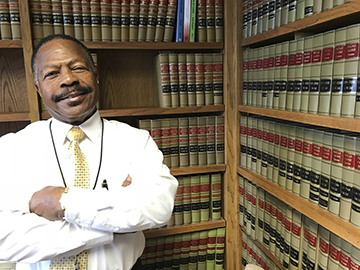

- Judge Donald Floyd relaxes in his office at the Jefferson County Courthouse in Beaumont. He is retiring his post as he has reached the state mandatory retirement age for his office. Ken Stickney/The News

BEAUMONT — The Honorable Donald J. Floyd has packed up his books, wall hangings and robes, preparing for the inevitable: retirement.

He’s presided over civil court in the 172nd District since Dec. 5, 1989, when he moved into an office he’s maintained at the Jefferson County Courthouse ever since. Now 75, the state mandatory retirement age for his office, the law will move him off the bench where he has served for 29 years. But it can’t keep him idle.

Floyd said he’ll apply for senior status and try to work part time around the region in the Second Administrative Judicial Region, which includes Houston, Conroe and points north and northeast, subbing as a judge where needed. He’ll stay busy, he said, and he leaves with no regrets.

Trending

“The citizens of Jefferson County have elected me to seven consecutive terms,” he said, since he replaced former Judge Thomas A. Thomas. “I appreciate the opportunity to serve and for what they have done for me.”

Divine guidance

It’s an opportunity to serve he might never have had, he says, had it not been for what he calls divine intervention. A 1962 honors graduate of Abraham Lincoln High School in Port Arthur, he’d considered teaching English at the college level and, for the first few years after graduation from historically black Dillard University in New Orleans — he’d earned a four-year, United Negro College Fund Scholarship while going there — he’d worked for the Louisiana Department of Public Welfare.

But Floyd had a friend who was practicing law, and who assured him that he, too, could succeed in that profession. He attended law school at Thurgood Marshall School of Law at Texas Southern in Houston, aided by a Ford Foundation Scholarship and, as he had done at Dillard, stayed on the dean’s list while attending.

Floyd said his success had started at home: 1000 W. 16th St. on Port Arthur’s West Side. There, his devoted grandparents — his grandfather was a custodian; his grandmother, a maid — had impressed upon him the need to be educated. His grandfather, born in 1895, could neither read nor write but he worked tirelessly, giving up much for his grandson’s advancement. He died shortly after Floyd started law school, but Floyd’s grandmother lived to see him graduate college, law school, practice law and rise to the bench. He said he always felt the need to make his grandparents proud.

Washington and back

Trending

Following law school graduation, Floyd worked a couple of years in the Justice Department’s Civil Rights Division in Washington, D.C., often traveling on the job to distant points in the U.S. to try fair housing cases. He loved the frequent travel, and the job itself — principally doing work to enforce the 1968 Fair Housing Act. He became a “Washingtonian,” he said, reveling in the city’s history, culture and restaurants.

But in 1974, he returned to Port Arthur and his aging grandmother, and entered private practice with two friends — the firm was Morrison, Floyd and Morrison — for almost a decade at 1015 Gulfway Drive. Theirs was a general law practice — they took the cases that came through the door, he said — which included criminal and civil work. He handled both with equal aplomb.

In addition to practicing law, he became active in the community, participating in his church — first St. Mary’s, then Sacred Heart when the churches merged — and with scouting, social clubs and fraternities. And, he said, he met his wife, the former Marie Comeaux, while an attorney. She worked at a savings and loan, then with a chemical company and finally, in personnel with Jefferson County.

The couple had two children: Kristi Lynn Hargrave and Karla L. Floyd. The first earned a doctorate and is a counselor; the second has passed the principal’s exam and is working in Port Arthur schools. His job permitted him to help with their care and raising; he and his wife provided family “back-up” to one another.

In 1981, he won a seat on the Port Arthur Independent School Board and in 1983, he was appointed to the municipal bench, the first African American to serve in the role of city judge.

His firsts were only starting. In 1983, he was appointed to the newly created Jefferson County Court at Law No. 3, the first African American to hold the judgeship; the following year, he was the first African American to win election to the countywide position.

Last stop: 172nd

On Dec. 15, 1989, with Thomas A. Thomas’ retirement from the 172nd District Court, Gov. William P. Clements Jr., a Republican, appointed Floyd, a Democrat, as his replacement. “He thought I was most qualified,” Floyd recollected. In November 1990, he was elected to the position — again, the first African American in Jefferson County — and kept the position until his retirement, which comes Monday.

Floyd said civil law cases — they involved such areas as taxes, real estate and personal injury — proved interesting. In preparation, he earned certification in civil law/personal injury from the Texas Board of Legal Specialization.

“I liked those cases. They concerned people having problems in their everyday lives,” he said. They also taught him something new about various aspects of the world as cases were presented in his court.

He has loved serving on the bench, too.

“There is always something new,” he said. “It’s never routine. Judges and lawyers get a chance to learn something new every day. A judge has to be on top of the facts, as the law applies.

“You need to know the law in each area. One day, it might be real estate, a contractual matter. The next day, it might be an 18-wheeler accident. You have to be up to par on that.”

Early challenge

Seldom did he encounter problems as a judge due to race. Once, in his early months on the job, a couple of people in the court refused to stand for him when the bailiff told everyone in the courtroom to rise for the judge. Eventually, after trying to reason with them, Floyd found them in contempt of court and sent them to jail. The judge became known as someone to respect.

“Once they found out that I would put people in jail, I never had any trouble,” he said.

As an African American practicing the law, he said, he owed much to the legacies of Elmo Willard III and Theodore Johns, two black attorneys and pioneers in their profession in Jefferson County who preceded him.

“They laid the groundwork for me to get where I am now,” he said. “They had to put up with some situations as how they were treated. They were good lawyers and did well.”

The two filed lawsuits to integrate universities and other public institutions; their images are captured on a statue in front of the courthouse where Floyd has served.

Floyd said he ran a fair and impartial court but he also drew up a list of rules — Judge Floyd’s Top Ten List of Things Not To Do When Examining A Witness — that emphasized and ensured decorum, order and common sense in his courtroom.

He used reflection and common sense in deciding his cases, as well, eventually learning to withhold judgment until he’d reviewed his decisions and been certain about how he had applied the law. He said he kept active cases in separate piles, and would not render a decision until he was certain about it.

“If it got to here,” he said, his hands over that imaginary third stack, “I was satisfied with it.”

What’s next

Floyd said he’s met with his successor, Mitch Templeton, a Republican who won election to the civil court in November. Templeton has practiced in his court for years, he said, and is a good attorney.

“He has spent some time with me here,” he said, and Templeton said he will call for advice when needed, just as Floyd sometimes called upon other judges for their developed wisdom.

“I will be glad to help him,” Floyd said. “He will have to set his own standards, what he wants to do, how he wants to do it. He’ll have to get a feel for it.”

As for himself, Floyd must get a feel for retirement. The Port Arthur City Council recently honored his long public service; councilmembers cited his fairness on the bench and leadership in the community. Mayor Derrick Freeman declared Dec. 18 as “Donald J. Floyd Day” in the Port Arthur, which was not the first time that has happened — Aug. 30, 1984 was also “Judge Donald J. Floyd Day.”

Floyd told the councilmembers he’d been appointed to his first judgeship in the city; later, outside the chambers, he said he felt like he’d come “full circle.”

This week, he gazed out the same office window that’s provided him a view for 29 years and remarked how that view has evolved. Fit and trim, he said he’s ready for what’s next.