Jack Brooks bio: Accent on effectiveness, honor

Published 12:59 pm Monday, May 6, 2019

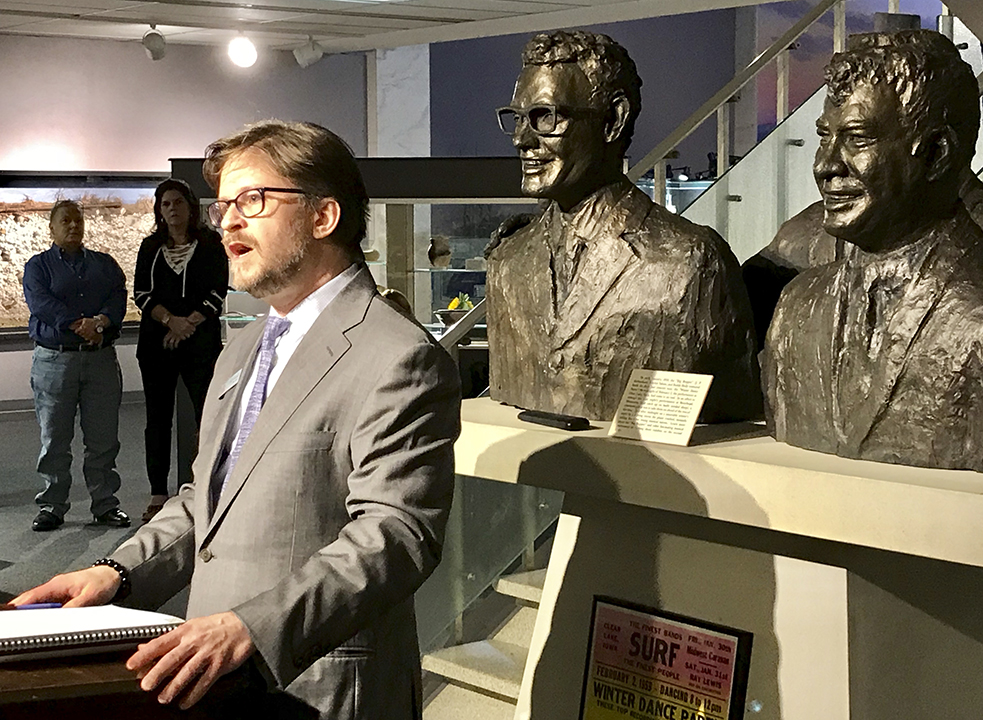

- Jeb Brooks, son of the former congressman, speaks at the Museum of the Gulf Coast on Thursday. (Ken Stickney/The News)

Nick Lampson said his initial effort to land an internship in the Washington office of former U.S. Rep. Jack Brooks, D-Beaumont, back in the 1960s flopped, but he wouldn’t take no for an answer.

For starters, Lampson had sent 46 letters of recommendation for the job, and he recruited additional advocates, shuttling their letters on Lampson’s behalf to his home congressman’s office. When Brooks traveled to Mid County for the opening of the new Groves Post Office, Lampson waylaid him there, stepping in front of the grizzled congressman on a sidewalk to introduce himself and renew his pitch for a job. Bad move.

“He got way into my space,” Lampson recalled Thursday night with a chuckle. “He said, ‘You send me one more G… d… letter, I’ll throw your file in the trash.”

Trending

A couple of weeks later, Lampson got word Brooks had OK’d him for an internship.

Lampson’s was one of many stories told about “The Meanest Man in Congress” on Thursday at the Museum of the Gulf Coast in Port Arthur, which hosted a book signing of a new biography of Brooks that carried that title. Business was brisk.

Brooks, D-Beaumont, served 42 years in the U.S. Congress, establishing a reputation as a gritty congressman of insistent integrity who worked, oftentimes away from the limelight, to protect the taxpayers’ investment in their government and to serve his constituents. Along the way, he mastered the art of forming coalitions among his colleagues to pass effective legislation of lasting impact.

Helping everybody

“You ought to be interested in helping people,” Brooks famously said, “but you ought to be interested in helping everybody.”

Trending

That’s what he did for four decades, a product of the Great Depression and World War II, where he fought as a Marine in the Pacific Theater, learning how to motivate men. Brooks, whose father died young, battled his way through college and then, as a young state representative, through law school in Austin, forging friendships among Texas political luminaries — Sam Rayburn was a mentor; Lyndon Johnson a friend — that served him well throughout his career.

That “meanest man” reputation was in jest — to a point — but reflected his tough stances taken in committee work on Capitol Hill. Go before his committees unprepared or in error and you’d best prepare for a grueling experience.

Co-author Tim McNulty — he wrote the book with his son, Brendan — said the book illustrates an era in Washington where members of Congress shared friendships across political lines, lived in the same neighborhoods and socialized together, and did horse-trading to pass their bills. In the Marines, McNulty, who covered Washington politics during part of his long career in the news business, said Brooks learned “who needed what and what he had to give” to effect trades to the benefit of the most people.

Attention to detail

Co-author Brendan McNulty, who works for the World Bank, said the book might have been written “10 different ways,” but they put much focus on Brooks’ impactful, commonsense work in drafting legislation that endures in areas such as transport regulations and safety procurement. He did so with great attention to detail and by forging bodies of support from large coalitions of his colleagues.

He did so while being fair but “tough as nails” in his work, someone trusted.

Lampson, who later served four terms in Congress, representing Jefferson County, said he learned much about constituent services from Brooks, who “helped people in their lives,” cataloged their requests for aid and followed up, always.

Tim McNulty said the authors were able to interview the retired Brooks perhaps a half-dozen times in Beaumont, after McNulty himself accepted a buyout with the Chicago Tribune and while he worked on the faculty at Northwestern University. Brooks, consummate horse trader, could relate to him the nuances of serving in Congress, where it was “not just about what you want, but about what the other person needs.” There was, McNulty said, value in the position that, “It’s not that I support you, but I won’t oppose you” — back when there was subtlety in serving on the Hill.

Brooks’ word

Jeb Brooks, the congressman’s son, said the book, published this year by NewSouth Books in Montgomery, Alabama, was well researched and fairly tells the story not only about what Jack Brooks accomplished in Washington, but the way in which he accomplished it.

“It’s about what it looked like inside when you elected good congressmen,” he said.

He related a story — it’s told in the book — about a meeting involving Brooks and his Democratic House colleagues, Tip O’Neill and Jim Wright, as they negotiated a deal on a bill with U.S. Sen. Bob Dole, R-Kansas.

When they forged their agreement, Dole insisted that O’Neill and Wright draft letters to him guaranteeing their end of the bargain. Wright asked him if he needed a letter from Brooks, too.

“Naw, Brooks’ word is good,” Dole replied.

He didn’t need it on paper.

Touch of mirth

Brooks also had some fun along the way. McNulty recalled a story of when Brooks’ neighbor, U.S. Sen. Strom Thurmond, R-South Carolina, told the congressman while strolling their neighborhood that he and his second wife, who was 44 years his junior, were expecting a child.

Brooks, with deadpan delivery, leaned over to Thurmond and asked, “Who do you suspect?”

Brooks might’ve gleaned that droll sense of humor from his mother, widowed young, who worked hard to support her family. The book recollects that once, when Brooks was visiting her in Beaumont, the phone rang and his mother went to answer it. Brooks told her to let it ring — “I wouldn’t answer it if Jesus Christ himself was calling,” he said.

“Don’t worry, dear,” his grace-filled mother told him. “If He called, it wouldn’t be for you.”