Forecasters grapple with getting it early — and right

Published 12:42 pm Friday, June 1, 2018

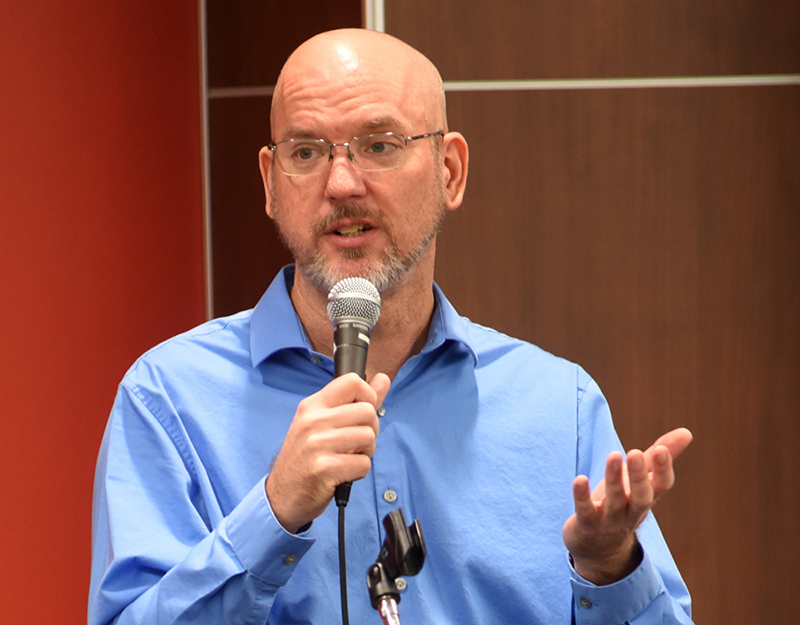

Forecaster Roger Erickson speaks to a workshop at Lamar University. Courtesy photo/Lamar University

Editor’s note: This story first appeared on April 29 in our special coverage, “Beyond the Storm.”

By Ken Stickney

ken.stickney@panews.com

BEAUMONT — Twenty-one names, Alberto to William, have been offered for storms in the coming hurricane season, but forecasters don’t expect to use them all.

Nonetheless, Roger Erickson, warning coordination meteorologist and senior forecaster for the National Weather Service in Lake Charles, expects a busy season. The NWS will release its look at the 2018 hurricane season on the third Thursday in May, before the season opens June 1.

Erickson, who spoke this week at a workshop hosted by the Center for Advances in Port Management at Lamar University, said to expect a “neutral” pattern in the Atlantic climate, a weather rollout similar to that experienced in 2008. That’s 2008, as in Hurricanes Gustav and Ike, which made landfall in Cocodrie, Louisiana, and Galveston on Sept. 1 and Sept. 13, respectively.

So expect some activity, perhaps named storms that number in the low teens, Erickson said. That’s for the entire Atlantic basin.

Typically, he said, about 100 tropical waves move across the Atlantic, so it’s important to be ready not only in August and September, when most focus is on hurricanes, but at other times, too — such as in April-May, when some unusual systems develop.

Trouble without hurricanes

But you don’t need a hurricane to find trouble, Erickson added.

“Harvey was a tropical storm when it did its most damage,” he said.

Erickson, since 1995 stationed at Lake Charles, which oversees the weather forecasts for Southeast Texas, said there have been evacuations from the area for wind and storm surge but not rainfall. Evacuations can come with Category 3 storms. That will change.

“That’s something we will have to address with community leaders,” he said. “What threshold should we use to evacuate before the rain gets here?”

And it will rain here, he said.

“In Southeast Texas, we always have a knack for a ton of rain in tropical seasons,” he said.

Erickson said internally, the NWS is discussing the best plan of action for coordinating with local governments. The idea is self-improvement at NWS and better services for those in their region, and no plan is likely until later this summer.

The goal, he said, is making communities in the Lake Charles region more resilient.

“Flooding,” he said, “is the biggest thing” — especially post-Harvey.

“Flooding is the biggest presidential declaration every year,” he added.

It’s a tricky business

Putting out those hurricane and flood warnings is tricky, he said. The NWS doesn’t want to alarm the entire Texas coastline with every storm, but wants to be more specific about where storms are headed.

“On how large of a coastline are we causing panic?” he asked. That’s what forecasters want to avoid.

For example, he said, Hurricane Rita in 2005 was predicted for landfall in Florida, then Brownsville, before striking between Sabine Pass and Holly Beach, Louisiana. Gustav in 2008 was, at one time, bound for Corpus Christi but hit Louisiana instead.

What has improved for warnings in recent years Erickson said, is predicting the track of the storm. But it’s not foolproof.

Three days out, he said, the margin of error is 150 miles; at two days, it’s 90. The one-day forecast error is 40 miles.

But Harvey, he said, was something else.

10-20 inches … at first

Between Aug. 23-30, Harvey dropped 40 inches on 3,643 square miles; it dropped 30 or more inches on 11,492 square miles; 20 or more inches on 28,949 square miles. In Nederland, it dropped more than 60 inches, more than any U.S. storm in history.

That’s for a storm that, for most of its development and travel, was predicted to drop 10-20 inches. But Erickson said such rainfall predictions carry with them a worst-case scenario of twice that rainfall.

In a “doozy of a hurricane season,” he said, Harvey became the most expensive hurricane in history, with a ticket price of $125 billion. Hurricanes Maria and Irma also ranked among the five most expensive hurricanes in history.

Harvey itself, he said, proved an elusive mystery for forecasters.

At one point, it was a looming rain event with 10-15 inches predicted over five days. Two days later, it was no longer a tropical system. Then it “regenerated itself,” presenting itself as a “Cat 4” hurricane. In short, he said, it was “finicky.”

“They all have unique characteristics,” he said. “They are all unpredictable.”

When it made landfall at San Jose Island, then Rockport on Aug. 27, it indicated big rainfall numbers: 10-20 inches. Then things got worse. You remember.

More explanation

Erickson said the Lake Charles office did the best they could, given the unpredictability of the storm.

“We knew it would be a big rain event. When you talk about big numbers — 30-50 inches — to express what that means to a community: houses and businesses flooding, people trapped in houses … That’s part of why we need to do a better job explaining,” he said.

The stakes are high along coastlines, whether they involve residential development, like in Florida, or industrial, like Port Arthur. Given the traffic along the Sabine-Neches, liquefied natural gas, petrochemicals and more, trouble here can affect the national economy.

In Harvey’s aftermath, some scientists said Harvey may be the storm of the future, as coastal communities might expect fewer but larger storms. Erickson seemed unconvinced.

“It’s difficult to say if storms have changed,” he said. “Groups of scientists try to forecast way in advance but there is still a lot of debate out there.

“Subtle climate changes, like seas rising, happen over decades or hundreds of years. It’s hard to forecast so far ahead of time.

“We’ll all be gone before that happens.”