BLACK HISTORY MONTH — Education career brings Glenn Mitchell back home

Published 12:15 am Friday, February 7, 2020

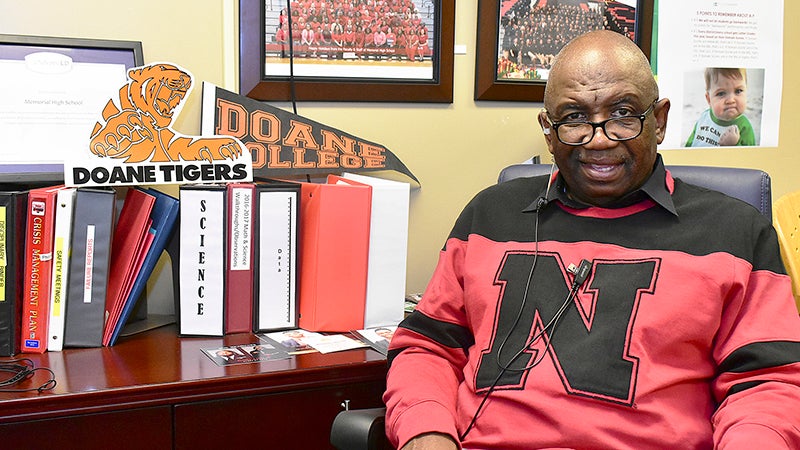

- Memorial High School Principal Dr. Glenn Mitchell was a standout football and track athlete at Doane College, now Doane University, in Nebraska, from 1966-70. Mitchell earned a doctorate degree from the University of Nebraska, which is represented on his sweatshirt. (I.C. Murrell/The News) 2-6-20

(Editor’s note: This is the first in a four-part series spotlighting African American leaders as part of a Black History Month profile series.)

A moment of rejection in the life of Glenn Mitchell led to an opportunity that opened the door for the seventh-year Memorial High School principal to build a long educational career.

Shortly after Mitchell won the district 440-yard championship for Lincoln High School in 1966, the track and field coach at Lamar State College of Technology talked to the young Port Arthuran.

Trending

“Ty Terrell was the big name around this area,” Mitchell said. “He was from Port Arthur. Gerald Williams was an all-state hurdler from Lincoln who went to Lamar. Gerald was all hype, saying: ‘Aw, man, you’ve got to come to Lamar. This will be great. We can get back together again because we were on the mile relay team together at Lincoln.”

By Mitchell’s account, Williams wasn’t as enthusiastic about Mitchell, aside from offering his congratulations on the district title.

“Just to my face, he told me, ‘Well, I don’t think I’m going to offer a scholarship at this time. He said to Mr. Clayton Clark, my track coach at the time: ‘It’s because Mitchell is kind of a clumsy runner. He’s kind of awkward.’ So, he took the guy who was third place.”

The third place runner, Mitchell recalled, was Waverly Thomas of Galveston Central.

Mitchell leaned toward working at a refinery after high school, but Clark talked him out of that. Down but not out, Mitchell ran a 49-second 440-yard dash at the Baytown Relays the next week.

“That was blue-chip, man,” he said. “If you compare the times of the Lincoln athletes to the times of the Thomas Jefferson athletes, there’s a world of difference, but they were able to get some much better offerings than we had.”

Trending

Pipeline to Doane

A member of the Lincoln class of 1965 who had come back home from Illinois told Mitchell about a small college in Crete, Nebraska, that recruited him for track.

“[Al] Papik gave me a call, but he spoke to my grandmother,” Mitchell said of the Doane College football and track coach. “He didn’t say anything to me. He told my grandmother, ‘Well, I’m offering scholarships for kids who are interested in coming to Nebraska.’ He mentioned Paul Broussard, and she knew Paul. She said to coach Papik, ‘Well, sure, he’ll be there. You tell me when and I’ll get him there.’ As she hung up with him, I told her, ‘Well, you didn’t ask me.’ She said, ‘I didn’t have to ask you. That’s where you’re going.’”

Mitchell hopped on a train with a shoebox with chicken and cried all the way to Dallas, questioning whether his grandmother loved him for sending him where she had never been before. The rest is history, he said.

While competing for Doane at a Des Moines, Iowa, track meet, Mitchell ran into an old recruiter — Terrell.

The prestigious Drake Relays in 1968 would be the last time five of Lamar’s athletes competed. Flying through rain from Des Moines overnight into April 28, a twin-engine Beechcraft Queenair private plane carrying the athletes including Thomas, 20, and John Richardson, 20, of Port Neches; Terrell, 46; and pilot Eleric Winston McCall, 46, crashed into a rice field near the Beaumont Municipal Airport. McCall suffered an apparent heart attack and died, while the other six were killed instantly.

Williams was injured and didn’t make the trip.

In football Mitchell played tight end, defensive end and kickoff kicker on Doane Tigers teams that went 33-0-2. Doane’s track team also won the Nebraska Intercollegiate Athletic Conference each year Mitchell was there, he said.

Broussard’s and Mitchell’s experience began a pipeline of athletes from Lincoln High to what is now Doane University, including Larry Green, Michael Sallier and Ron James.

“No one would give us a shot at anything, and [Papik] took a chance,” Mitchell said.

Education career

Following graduation, Mitchell went into teaching and coaching football, basketball and track at Horace Mann High School in Omaha, Neb., for five years.

“I don’t think we ever lost a track championship in my tenure as a coach,” Mitchell said.

He then went into administration and pursued postgraduate degrees including his doctorate from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln. He became a principal and director of human resources before retiring from Omaha Public Schools in 2000.

Around that time, the school district in Kansas City, Mo., asked if Mitchell would become a consultant for its alternative schools.

After talking with his wife and Lincoln classmate, the former Carol Taylor, Mitchell agreed to take the position, and a one-year stay became a nine-year stint in which he was promoted to assistant superintendent for student personnel services.

In 2013, the Port Arthur Independent School District asked Mitchell about his interest in becoming principal at Memorial. Mitchell never second-guessed his desire.

Memorial assistant principal Dwight Wagner, a Port Arthur native, did not know Mitchell until joining his staff in 2018.

“I think it was a divine connection,” Wagner said. “I had retired after 39 years of working in the district, and in April of 2018, Dr. Mitchell called and asked if I would serve as a substitute for an assistant principal who was on sick leave. … After praying about it, I said, ‘OK, I would give it a shot.’”

Formerly the principal at Dick Dowling (now Port Acres) Elementary, Wagner has taken to Mitchell’s on-the-job humor and wisdom.

“I call him King Solomon because when you’re in that seat and people are coming with all these different problems and you wonder, ‘How is he going to solve this one?’ he finds a way. He knows how to be the traditional African American father of the ’50s and ’60s — ‘Come here, boy, and listen to me!’ — and then after listening, he has that soft side. He doesn’t like to show that soft side often. He’ll sit and say, ‘Son, listen, what do you plan to do with your life?’ He’s got that good balance.”