Ex-Hoya from Port Arthur recalls “so much more” to coaching great John Thompson

Published 12:16 am Friday, September 4, 2020

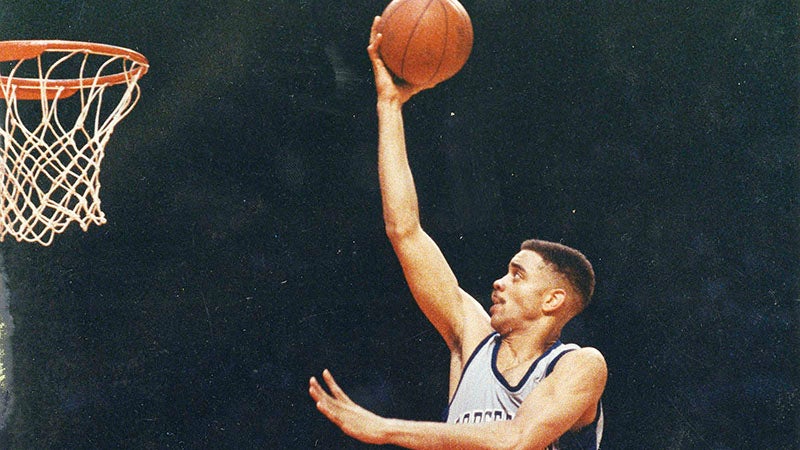

- Anthony Allen, pictured during a 1989 game, played under John Thompson Jr. at Georgetown from 1986-90. (Georgetown University)

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Anthony Allen once told Georgetown University officials he would sign with the Hoyas’ basketball program out of Port Arthur’s Lincoln High School if then-head coach John Thompson Jr. came to speak at the Bumblebees’ state championship banquet in 1986.

“It is a true story,” Allen said on what would have been Thompson’s 79th birthday Wednesday (Sept. 2). “I think he shocked Port Arthur when he came down. He spoke to everybody. At one time, it looked like that whole speech was directed to me. He expected his athletes to go to class, come in and do well on the basketball court and graduate. Everyone took that to heart.”

Allen held his end of the bargain and spent the next four seasons competing under Thompson in Washington, D.C.

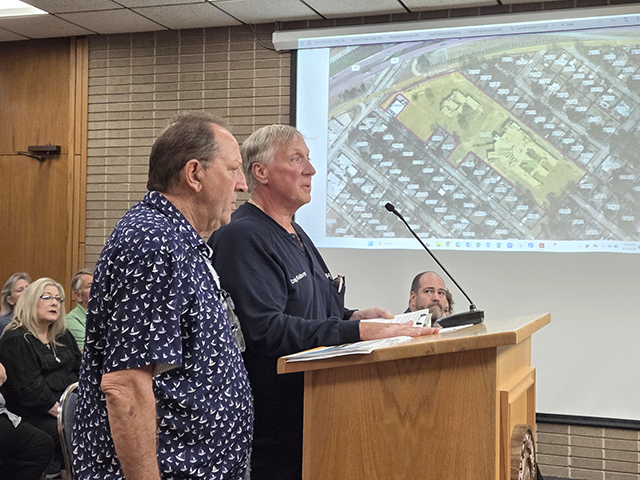

An undated, framed photo hanging in the hallway of James Gamble’s home on April 3 shows then-Georgetown basketball coach John Thompson Jr. autographing a ball for Gamble, who at the time was head coach at Lincoln. (I.C. Murrell/The News)

Thompson, who made history in 1984 becoming the first Black head coach to win an NCAA Division I basketball championship, died Sunday (Aug. 30), his family confirmed through Georgetown. The cause of death was not announced.

The 6-foot-7 Allen was named Mr. Basketball in Texas as a senior at Lincoln and finished his high school career with two state championships. His first came the same year Thompson’s Hoyas knocked off Hakeem Olajuwon-led University of Houston in the NCAA final in Seattle, 84-75.

That was the second of three championship games in which Thompson led Georgetown in a four-year span. The Hoyas lost 63-62 to the University of North Carolina on Michael Jordan’s go-ahead jumper in 1982 and was stunned 66-64 by Big East Conference rival Villanova University in 1985.

Thompson stood for so much more than basketball, even if he stood for it within the basketball realm, Allen recalled.

“The great shooters, we took their best shooter away from them,” Allen said. “That’s the way Thompson lived his life, full press forward, whether it was speaking out against discrimination and helping people in the D.C. area and giving away turkeys.”

Allen recalled standing on the court when Thompson walked off from a January 1989 game against Boston College to protest NCAA propositions 42 and 48. Prop 48, which went into effect in 1986, set minimum grade point average and standardized test score requirements for eligibility during one’s freshman season of college competition. Prop 42, adopted in 1989, eliminated athletic scholarships for those who partially qualified under Prop 48, but was rescinded the next year.

“[Thompson] felt it discriminated against lower-income and especially black athletes,” Allen said of the propositions. “He wanted everyone to have an opportunity. With the opportunity comes our success. He believed everyone deserved the opportunity to succeed.”

James Gamble, who coached Lincoln to four state titles between 1981-88, said his team’s style of play was similar to Georgetown’s under Thompson, noting the ability to score off turnovers caused by pressure defense.

“A lot of kids played and had an opportunity to get on the floor,” Gamble said. “The thing he really said to us [at the banquet] was it appealed to him we had character. He was impressed with the effort we gave on the floor, the camaraderie the kids had with each other. You could understand why we won because of the impression he got.”

That Thompson came to Lincoln on more than one occasion to recruit showed how much the Bumblebees impressed him, Gamble said.

“I was certainly impressed with his teams,” he said of Thompson. “… Everybody would like to win a championship, period. There was no question. I saw as many Georgetown games as I possibly could. There was no doubt of his ability to coach and his professionalism, period. The kids he recruited were first class. He had a well-run organization.”

Only four Black head coaches have won NCAA Division I titles in men’s basketball. Nolan Richardson of the University of Arkansas followed Thompson’s accomplishment in 1994, Tubby Smith returned the University of Kentucky to glory in 1998 and Kevin Ollie carried the University of Connecticut to the top in 2014.

“It’s always pleasing to see a black person succeed,” Gamble said. “They used to say our lack of knowledge of the game, or our inability to play, but to see John Thompson succeed like that was more proof we can do as well as anybody when given the opportunity.”

Allen, who lives in Dayton, Maryland, and works as a patrol officer on the Georgetown campus, was left in awe over Thompson, the complete person.

“ESPN is on today because of the things the Big East [Georgetown’s conference] accomplished,” Allen said. “It brought us to the forefront, just as it brought Nike up. [Thompson] was even negotiating other people’s contracts. He was such an individual with so much depth.

“In this day, he made being a tough black man functional. That speaks to this generation more than anything.”